njak 100

Wednesday, 25 May 2016

Beware the slow train to Inertia Central

High Speed 2, the UK’s nascent national high speed rail network, is on the cusp of tangibility. No less than £12bn of civil works contracts for the first phase of the planned 540 km railway await sign off from HM Treasury. But much more important than that, it has started to hint at generating the kind of momentum its detractors long scorned as impossible: it is reportedly inspiring school pupils in Crewe, catalysing an inward investment agency in Birmingham and spurring fashion house Burberry’s production expansion in Leeds.

At such an important, and indeed delicate, juncture, it can hardly come as a surprise that the advocates of fudge and procrastination are once again mustering their troops in support of a Manifesto of Muddle. They may be encouraged tacitly by the Treasury, which – predictably and unsurprisingly – is bridling at the notion of a long-term, regionally-focused infrastructure programme. To adapt an infamous euphemism said to emanate from number 11 Downing Street, HS2 is not a mini-roundabout.

Today, a group of academics and transport specialists convened by veteran railway timetabling consultant Jonathan Tyler has set out its effort to stymie the progress of HS2 in favour of what its group suggests should be an ‘independent review’ of the project. A 10-page dossier has been circulated to the trade press and, presumably, policymakers in advance of the public release on May 26; its contents are a summary of the conclusions of a workshop held at the University of York, my own alma mater, earlier in the year.

Tyler & co’s dossier initially appears to be more akin to an executive summary, yet that would imply that it offers a plan of action, when surely the reverse is true. ‘The Case for a Review’ is more nuanced title, and the document eschews emotive calls for HS2 to be cancelled, deferred or even halted. Work could continue in some form while a ‘review’ on the authors’ preferred terms is completed; this would then assess whether some, all or none of HS2 should continue.

The authors are clearly experts in their field, and clearly their conclusions should not be lightly dismissed. The dossier is as subtle as it is elaborate in its efforts to convince us that ‘alternatives’ to HS2 have not been assessed, that trains on Europe’s busiest mixed-traffic railway are mostly empty, or that scant international evidence exists to support the wider socio-economic objectives of HS2.

Indeed, the dossier, and no doubt the workshop which preceded it, are likely to easily convince those whose view of the rail network is influenced by a career during the years of managed decline, or whose eco-agenda suggests that the best kind of transport policy advocates no movement at all. To them, HS2 is clearly a gold-plated outlier, rather than a further exemplar of a mature and proven technology encompassing more than 20 000 km of successful operation in 18 countries where average speeds exceed 160 km/h.

And if there is a reason why some of the messages in Tyler’s report seem rather familiar, perhaps it’s because they are. Deftly conveyed with a gloss of academic respectability they may be, but there is little here that has not previously been addressed. And where the mask slips, some of the assertions are quite astounding. Under rail capacity, for example, the dossier argues that:

‘Euston, King’s Cross and Marylebone are the least crowded of all London termini, with a load factor on Virgin West Coast of less than 40%’

The simplistic use of load factor as a proxy for route capacity has been a standard tactic for attacking HS2 since its inception. The report cites ORR data from 2014-15, just after a programme of train lengthening from nine to 11 cars was completed by VWC, clearly implying a lag in occupancy while the market catches up. Had it not done so, the recent decision to install visual representation of seat occupancy on the departure boards at London Euston would be a curious move.

But more pertinently, the completion of both planned phases of HS2 would bring capacity relief to routes covered by approximately eight passenger franchises, so why would such an earnest report assume evidence of one is somehow representative? And lest we forget, as perhaps Tyler et al have, it is not load factor that has caused the cessation of passenger services at stations in Staffordshire in the last decade, or the axing of through trains at rush hour between mid-Cheshire and central Manchester.

Equally eyebrow raising is the revival of the moribund 51M proposal to increase WCML capacity through train lengthening and a series of incremental interventions along the route. Tyler claims this resulted in a benefit:cost ratio of 5.2, yet a peer review by Atkins subsequently reassessed 51M’s rolling stock assumptions and revised this down to just 1.6. This is not mentioned.

Perhaps most egregiously, the authors suggest that unspecified ‘new construction procedures’ mean that national infrastructure manager Network Rail can undertake ‘large projects without disproportionate changes to the everyday delivery of a train service’. They cite recent work at Norton Bridge (the £250m Stafford Area Improvements Programme) and the rebuilding of Reading station, leaving us to infer that the incremental total route modernisation approach should again be pursued, perhaps on the East Coast Main Line, where Tyler et al worry that investment could be deferred.

The isolated citation of Stafford and Reading is an appalling distortion of the context of recent railway investment, and the authors should be ashamed that they have resorted to it. This blog has already outlined the clear lessons of the Great Western Route Modernisation programme, while in the Midlands, the Stafford grade separation and rebuilding of Birmingham New Street have accounted for £1bn of expenditure and yet failed to yield a single extra peak hour train path between them. I find it hard to believe Tyler and his acolytes do not appreciate this.

Similarly predictable are a series of well-trodden tropes around sustainability, most of which focus on macro-policy outcomes (reducing the need to travel, imposing the marginal cost of transport etc), while neglecting specific practicalities (HS2, or any other electric railway service, is going to be much greener if it is powered by renewable energy, yet this is not addressed). The 400 km/h design speed is predictably invoked, alongside an assertion that lower design speeds are applied in France and Germany, and such an approach would permit ‘a less damaging route’. This blog for one remains to be convinced that a more sinuous, and almost certainly longer, alignment would reduce environmental impact, nor that more braking and acceleration would be ‘greener’.

Needless to say, the authors indulge in a well-rehearsed sleight of hand in failing to inform us that the timetabled operating speed is planned to be closer to the current international standard of 300 km/h to 330 km/h, as confirmed on the record by HS2 Ltd Technical Director Prof Andrew McNaughton.

Their report is on more consensual ground when it assesses social and economic impacts and the vagaries of economic rebalancing. But it is surprising to see that it relies strongly on citations from Prof John Tomaney at the Transport Select Committee that are now five years old, and other work – especially the World Bank’s assessments of the economic effects of China’s high speed rail boom – continue to be eschewed.

As a Rochdale native though, it is pleasing to see my home town get a mention, but the assertion that infrastructure designed to connect cities may indeed benefit cities like Manchester or Leeds is self-evident in an era of ongoing urbanisation. The authors seem to believe, as many HS2 critics do, that the railway is somehow an ‘isolated’ entity, rather than one which can plug into diverse networks at key nodes. It is noteworthy, but not mentioned in the dossier, that every one of HS2’s ‘out of town’ stations is planned to be served by urban rail routes.

The economic development of places like Bradford or Rochdale is surely bound into that of the nearest big cities, and it is desirable for new infrastructure investment to facilitate regional mobility by removing capacity-eating long-distance traffic to dedicated routes and releasing capacity on existing corridors. This must remain an overarching objective of HS2.

Lastly, our authors offer a salutary lesson about the future, where ‘external factors’ may begin to influence project appraisal processes. These too are a rehash of the eminently predictable: the use of travel time, the rise of digital technology, autonomous vehicles etc. ‘These uncertainties could rapidly multiply to the point where a favourable outcome from such a large project was most unlikely.’

What an inspiring message for those schoolkids in Crewe. The future’s suddenly become particularly unpredictable, boys and girls, so…er, best not bother.

The Treasury must be rubbing its hands in glee at the prospect of such a ringing endorsement of the cult of patch and mend.

Friday, 15 May 2015

Northern Powerhouse must include HS2

Few phrases have been uttered more frequently in the wake of May 7’s general election than ‘the Northern Powerhouse’, a package of devolution proposals intended to decentralise government towards cities from Westminster. At the time of writing, transport – and specifically rail – is at the forefront of the plans, having also been a central plank in various policy reports issued over several years by bodies such as IPPR North.

The role of rail in the Northern Powerhouse focuses less on transport user advantages and instead accentuates wider economic benefits, such as improved labour market connectivity and agglomeration gains identified in other large semi-integrated conurbations, such as Germany’s Ruhr Valley region and the Dutch Randstad. Such philosophy has led the previous and current governments to back plans to invest up to £15bn on enhanced rail links between northern cities, but in practice this had coalesced into various options for new or very extensively upgraded corridors between Manchester and Leeds. This has, in turn, predictably led to calls for a ‘Crossrail of the North’ to be prioritised ahead of other railway projects, notably the second phase of High Speed 2. Indeed, economists and business commentators now take the benefits of some form of ‘High Speed 3’ advancing while HS2 is gleefully cancelled as almost absolute truths.

The ubiquitous Christian Wolmar aside, few transport commentators are so quick to leap to this conclusion, and with good reason. First, there is the blunt reality that rail’s most established and commercially-viable market is serving London, which is the origin or destination for almost two-thirds of all passenger-journeys. The corollary of this market reality is that the economics of regional railways are much more fragile, since volumes are less and yields lower. This in no sense undermines the case for improving rail links in the regions, but it does mean that major infrastructure works which do not have a ‘baseload’ London market attached to them are going to be more delicate to deliver.

The hurdles facing HS3 can be put into context by the highly unusual bureaucratic intervention required to ensure the replacement of the much-maligned ‘Pacer’ railbuses could be included in the next Northern passenger rail franchise. A letter released by the Department for Transport lays bare just how little of the benefits of new trains can be captured by established transport business case methodology.

Which brings us back to wider economic benefits. These ‘WEBs’ form a relatively small part of the economic case for HS2, which would link London with Leeds, Manchester and points north in a 540 km network centred on Birmingham. The chronic shortage of paths (let us not be distracted by load factor, a capacity red herring) on our north-south main lines, and the comparable cost of vastly less effective incremental upgrading schemes have ensured HS2 has made it to the hybrid bill committee stage, for the first phase at least.

Some of these issues can help spur the HS3 idea too, but if we are serious about improving non-London connectivity then the merits of HS2’s second phase must not be so routinely overlooked. The most stark comparison is to assess connectivity in the triangle between Leeds, Birmingham and Manchester. Today, there a whopping eight trains per hour linking Leeds and Manchester taking three different routes. Of these, five are express services with a standard timing of around 50 min. Contrast this with the Birmingham – Leeds axis, where only one train typically operates each hour and the journey time is almost 2 h. HS2 would cut that journey in half and offer at least twice as many trains – not that you’d know that from any media outlet whatsoever, including HS2 Ltd’s own communications team.

More pertinently still, HS2 has a key role to play in fostering the Northern Powerhouse itself by connecting the Sheffield/Barnsley/Rotherham area (assuming a Meadowhall station) with Leeds and York, while connections to the East Coast Main Line at Colton pave the way for a reduction in Newcastle – Birmingham travel times of around an hour, again with improved frequencies. And DfT and rail industry groups have long suggested that electrification can enable HS2 to be plugged into the cross-country network too, with trains originating in Bristol or Cardiff and sharing the new railway between Birmingham and York. A link with the conventional network in the Washwood Heath area of Birmingham to enable this should be added to the ongoing legislation for HS2's first phase.

Us northerners should nevertheless take heart that the wider economic benefits of rail investment, which for HS2 have been so roundly castigated by some in the London commentariat, are after all strong enough on their own to justify some form of HS3. But it would be exceptionally myopic to pursue this bold agenda for cross-Pennine connectivity while at the same time ditching more pressing enhancements, which include electrification, East Coast Main Line works and, yes, the northern sections of HS2.

The role of rail in the Northern Powerhouse focuses less on transport user advantages and instead accentuates wider economic benefits, such as improved labour market connectivity and agglomeration gains identified in other large semi-integrated conurbations, such as Germany’s Ruhr Valley region and the Dutch Randstad. Such philosophy has led the previous and current governments to back plans to invest up to £15bn on enhanced rail links between northern cities, but in practice this had coalesced into various options for new or very extensively upgraded corridors between Manchester and Leeds. This has, in turn, predictably led to calls for a ‘Crossrail of the North’ to be prioritised ahead of other railway projects, notably the second phase of High Speed 2. Indeed, economists and business commentators now take the benefits of some form of ‘High Speed 3’ advancing while HS2 is gleefully cancelled as almost absolute truths.

The ubiquitous Christian Wolmar aside, few transport commentators are so quick to leap to this conclusion, and with good reason. First, there is the blunt reality that rail’s most established and commercially-viable market is serving London, which is the origin or destination for almost two-thirds of all passenger-journeys. The corollary of this market reality is that the economics of regional railways are much more fragile, since volumes are less and yields lower. This in no sense undermines the case for improving rail links in the regions, but it does mean that major infrastructure works which do not have a ‘baseload’ London market attached to them are going to be more delicate to deliver.

The hurdles facing HS3 can be put into context by the highly unusual bureaucratic intervention required to ensure the replacement of the much-maligned ‘Pacer’ railbuses could be included in the next Northern passenger rail franchise. A letter released by the Department for Transport lays bare just how little of the benefits of new trains can be captured by established transport business case methodology.

Which brings us back to wider economic benefits. These ‘WEBs’ form a relatively small part of the economic case for HS2, which would link London with Leeds, Manchester and points north in a 540 km network centred on Birmingham. The chronic shortage of paths (let us not be distracted by load factor, a capacity red herring) on our north-south main lines, and the comparable cost of vastly less effective incremental upgrading schemes have ensured HS2 has made it to the hybrid bill committee stage, for the first phase at least.

Some of these issues can help spur the HS3 idea too, but if we are serious about improving non-London connectivity then the merits of HS2’s second phase must not be so routinely overlooked. The most stark comparison is to assess connectivity in the triangle between Leeds, Birmingham and Manchester. Today, there a whopping eight trains per hour linking Leeds and Manchester taking three different routes. Of these, five are express services with a standard timing of around 50 min. Contrast this with the Birmingham – Leeds axis, where only one train typically operates each hour and the journey time is almost 2 h. HS2 would cut that journey in half and offer at least twice as many trains – not that you’d know that from any media outlet whatsoever, including HS2 Ltd’s own communications team.

More pertinently still, HS2 has a key role to play in fostering the Northern Powerhouse itself by connecting the Sheffield/Barnsley/Rotherham area (assuming a Meadowhall station) with Leeds and York, while connections to the East Coast Main Line at Colton pave the way for a reduction in Newcastle – Birmingham travel times of around an hour, again with improved frequencies. And DfT and rail industry groups have long suggested that electrification can enable HS2 to be plugged into the cross-country network too, with trains originating in Bristol or Cardiff and sharing the new railway between Birmingham and York. A link with the conventional network in the Washwood Heath area of Birmingham to enable this should be added to the ongoing legislation for HS2's first phase.

Us northerners should nevertheless take heart that the wider economic benefits of rail investment, which for HS2 have been so roundly castigated by some in the London commentariat, are after all strong enough on their own to justify some form of HS3. But it would be exceptionally myopic to pursue this bold agenda for cross-Pennine connectivity while at the same time ditching more pressing enhancements, which include electrification, East Coast Main Line works and, yes, the northern sections of HS2.

Tuesday, 24 February 2015

HS2: McNaughton outlines the released capacity win

|

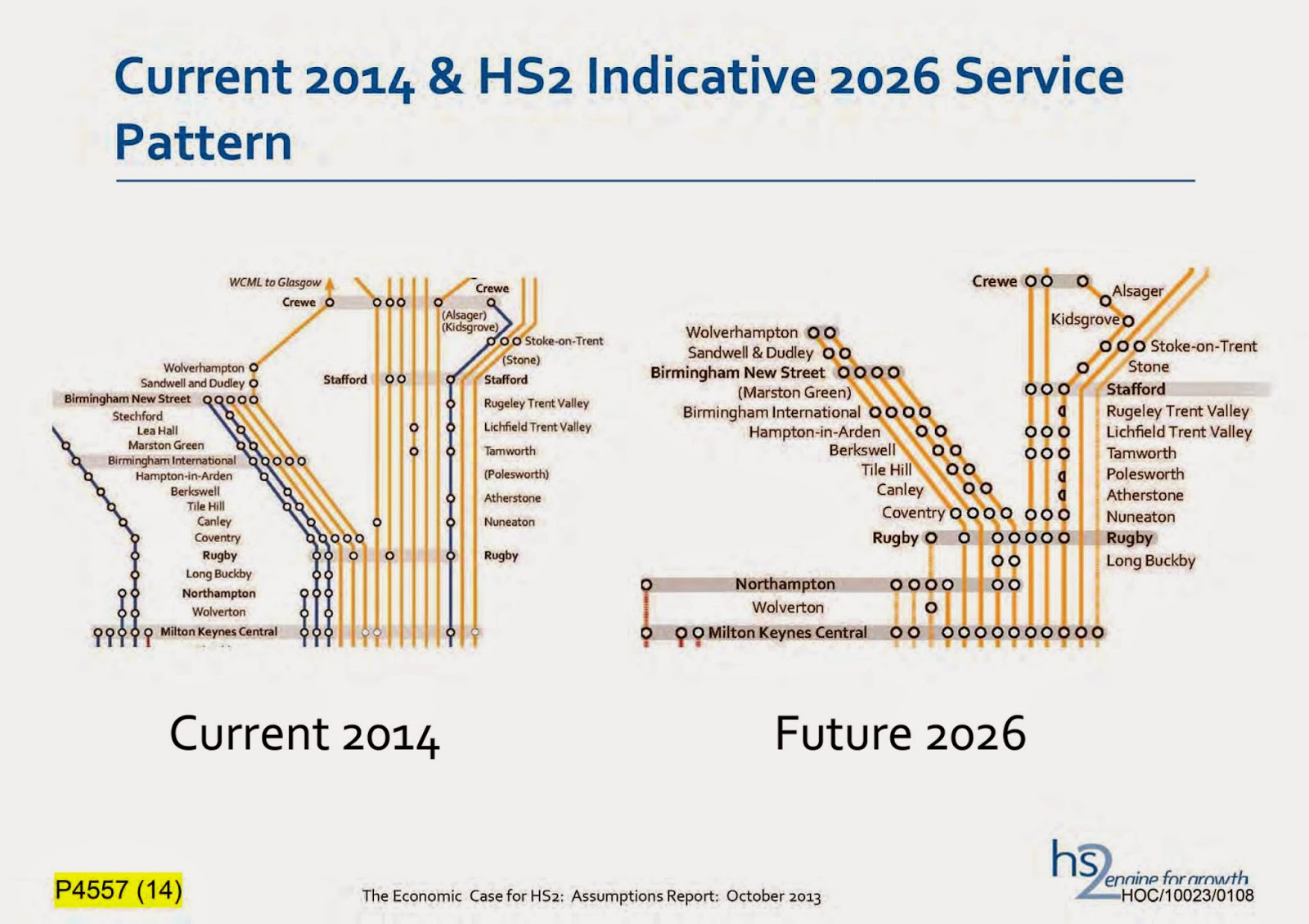

| Despite suggestions to the contrary by HS2 opponents, Prof McNaughton's slides made clear the increases in services which could be provided using capacity released by the first phase of the project. |

Professor Andrew McNaughton, Technical Director of the government's project delivery company HS2 Ltd, called it a ‘something of a canter’. But in reality, his appearance on February 11 before the committee of MPs scrutinising the first phase of the planned High Speed 2 railway network was a(nother) landmark moment, as it shone a light on one of the project’s most important assets.

In short, over these eight pages (pp41-49), McNaughton attempted to set out to MPs the nebulous, fraught and technocratic issue of ‘released capacity’. We hear it quoted so often as an advantage of HS2, but rarely do we see precisely how the hard bitten rail traveller – he or she with no inclination to board a long-distance train to London or Newcastle or Rotterdam or anywhere – might stand to benefit. And benefit a lot.

‘In each hour in the peak, because of HS2, there is the opportunity for the stations served by the West Coast Main Line to have around 6 000 to 7 000 extra seats. That is what released capacity equates to.’

McNaughton, not for the first time, sought to illustrate the issue by outlining, subtly yet effectively, how inefficiently our ‘patch and mend’ policies have led us to use our most strategic infrastructure, in the case the (notionally-upgraded) West Coast Main Line. In doing so, he drew a parallel with the country’s most capacious railway, London Underground’s Victoria Line.

‘If you recall, a few minutes ago, I said, in theory this is all non-stopping trains all going at the same speed, two minutes apart. You could end up with 30 trains an hour or, if they’re all stopping like the Victoria Line in the London Underground, 30 trains an hour. The practical limit on the WCML [fast tracks] today is 11 long-distance trains and four outer commuter trains, and there are trains on the slow lines as well. I’m going to concentrate on the fast lines. 11 plus 4 is 15.

'What does HS2 release? We take off the main line most of the long-distance non-stop services, because the purpose of HS2 is to serve cities on the long-distance network. That means in the peak we see at least 10 totally new services are available in the capacity that we released on the WCML.’

So, in a nutshell, we have a situation where we have a very old, but very expensively modernised, railway operating significantly below its theoretical capacity. That’s path occupancy of course, whereas much media brouhaha has focused on the question of seat occupancy or load factor. McNaughton addressed this too, noting that the provision of seating is a function of the number of train paths the railway is able to offer up. So needless to say, more seats might be occupied if more intermediate stops were inserted into long-distance trains on the WCML. Easy, right? Wrong:

‘The practical capacity is an operational capacity and this is not a fixed function for any particular railway; it is a function of how train services are planned on that infrastructure. I give some examples of how the way train services are planned affects the number of trains, the number of seats per hour, the number of stations, whatever, that can be served on a route.’

And the problem with the WCML – and the three other principal rail arteries HS2 would relieve in its second phase – is that, as McNaughton showed in his slides, it has to serve places en route, the ‘points A, B, C and D’ he cited. In commercial reality, B, C and D get a pretty raw deal: very few Virgin Trains expresses heading to or from London stop much south of Stoke, Crewe or Warrington. If they did, McNaughton reported, they would compromise the available paths for the two or even three trains behind. Then of course, any perceived load factor deficit would immediately evaporate.

As this blog pointed out recently, there is no longer any regular direct rail service between Watford and any destination in northwest England. A clear opportunity for the kind of inter-regional service which could (and in my view should) be offered in one of the 10 freed-up paths indicated by McNaughton.

It cannot be repeated enough that the fundamental usage of HS2 is already established. The services that will use it will in fact look remarkably familiar: faster and much, much more reliable, but still three fast trains from London to Birmingham and three fast trains to Manchester. The business case is a transferral and enhancement, not the dreaming up of a new market.

Indeed, of the 30 stations proposed to be served by HS2 trains once both phases are open, 21 are exactly the same stations as served by the equivalent services today (Warrington, Glasgow, York, Newcastle, London Euston and Manchester Piccadilly are among those in this group).

Unsurprisingly, and without reference to the slides that accompanied McNaughton’s presentation, those who remain dogmatically opposed to the HS2 programme leapt before looking. Others have highlighted the gross misrepresentation of Stop HS2’s description of McNaughton’s presentation, but such heat and light obscures the reality that our time-honoured patch and mend philosophy has led us to spend £10bn on a railway which afterwards defies efficient or reliable operation.

As we near the frenzy of a General Election campaign, primary evidence of a technically-credible nature is sure to be in short supply. Like Chris Gibb’s landmark report before it, McNaughton’s contribution is a vital one. HS2 can herald not just a highly-effective railway in its own right, but it can also unlock the potential of our legacy network. It must be built.

Thursday, 18 December 2014

CP5 cost crunch reinforces HS2 case

|

| Concerns about the cost and complexity of the Great Western Route Modernisation echo the problems of the incremental upgrading on the WCML. Photo: A Benton |

But by the middle of last summer, train operator First Great Western was running a high-profile advertising campaign, adorned with images of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, which touted a ‘massive’ £7.5bn investment by Network Rail in the route. Yet when newly-appointed NR Chief Executive Mark Carne spoke to parliament's Transport Select Committee on June 9 last year, he was forced to admit that he ‘did not have a fully-defined cost’ for the investment programme.

Some details of the problems are starting to emerge, and it is already apparent that other enhancements to the conventional rail network are also imperilled by a spiralling cost control issue. According to reports last August by The Sunday Times newspaper and industry newsletter Rail Business Intelligence, the cost of electrifying (some of) the Great Western Main Line has already grown from £1bn at the outset to £1.5bn as detailed design work has proceeded. Industry insiders suggest that other wiring schemes, covering the trans-Pennine and Midland Main Line routes, could be similarly affected.

This salutary tale ought already to bring back memories of Railtrack’s ill-starred efforts to modernise the West Coast Main Line from 1998 onwards at a supposed cost of £1.4bn. The out-turn cost was more than £9bn by the time of the project’s formal completion, but another £1bn has been spent subsequently on improving the resilience of the route. For the avoidance of doubt, NR is doing and will continue to do a vastly better job of managing Britain’s rail infrastructure than Railtrack ever did. But there is equally no doubt that that the cost and complexity of upgrading legacy railways to deliver more capacity is continually and routinely downplayed.

It is remarkable that the GW programme’s budgetary transition from £5bn to £7.5bn to ‘unknown’ in just three years appears to have been somewhat blithely overlooked. Claims that there are a plethora of ‘cheaper and easier’ alternatives to the High Speed 2 project remain common currency, despite the emphatic passage of the HS2 Phase I hybrid bill through its second reading in parliament earlier this year. In reality, the overwhelming body of evidence is that the true ‘blank cheque’ rail projects are those ‘patch and mend’ options which this blog has always insisted are unsuitable for the busiest rail arteries.

The limitations of the incremental upgrading are especially acute where there is need to deliver real-terms increases in capacity. Despite the now familiar wrangling about load factors (the relevance of which has been dented by the metric being ignored in Sir Howard Davies' aviation capacity reports), this in practice almost always means more train paths, whether for passenger or freight. It cannot be right that this is achieved overwhelmingly by ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’. On the upgraded WCML for example, paths are so scarce that an engineering-led scheme to raise the maximum speed of commuter trains to 110 mile/h was required to flight an extra train per hour to and from London Euston between Virgin Pendolinos. And to that extent, it worked. But the unintended consequence was to deprive Watford of the direct services to northwest England which it had enjoyed throughout the 20th Century. Whatever advantages this confers, improving non-London connectivity is clearly not one of them.

On the Great Western meanwhile, whatever improvements are made to the main line to Bristol and south Wales (note that the ‘Berks & Hants’ line route to Devon and Cornwall gets only a stub-ended electrification and almost no capacity or speed enhancements, which is a story in itself), there is a crux looming at the London end, as longer-distance traffic vies for capacity with intensive Crossrail suburban trains between Reading and London. Only a fool would bet against more messy capacity compromises, which is understandable since significant net gains in paths on the busiest sections of the route are simply not deliverable, despite the scale of the enhancement works.

All of which leads to fairly obvious conclusion. First, that the challenges faced during the ill-starred West Coast upgrading were not, as some HS2 critics claimed, an aberration. Stories of shifting specifications and engineers ‘not finding what they expected on the ground’ continue to swirl around the Great Western and other projects where major capacity enhancement is expected from an existing corridor. Second, with the GWML project in all its various elements now likely to reach a capital outlay comparable to WCRM, how can anyone rationally believe that replacing HS2 with a further plethora of ‘incremental’ upgrades represents fiscal prudence? With HS2 providing guaranteed capacity relief to at least four main line corridors, the implications of Network Rail being tasked with the same job are daunting. With NR’s debt now officially on the government’s books, the long-term cost of backing politically-expedient ‘patch and mend’ projects has just gone up a bit more.

With a general election looming, some observers are already stretching credulity by calling for HS2 to be halted. It is already clear that this would be rank bad policy.

Monday, 28 April 2014

Why MPs should back HS2 today

|

| All about London? A possible departure board at Birmingham Curzon Street after both phases of HS2 are completed. Image: Birmingham City Council |

Will the project benefit the north, the south or both?

Both. Much attention has been focussed on the notion that the project might 'suck business activity from the north towards London', yet there is in reality no consensus on these effects, not least because there can be no direct comparison between the UK's economic geography and that of any other country. Taken to its logical conclusion, the notion of London 'winning out' from HS2 would imply that those cities with inferior connectivity with the capital would somehow be insulated from these negative effects. That rather contorted argument has been put firmly in context by the recent campaign to restore rail links between London and southwest England – there were few suggestions that rebuilding the railway through Dawlish might somehow drain the economy of Devon and Cornwall.

The lessons from the 17 000 km of high speed railway in use internationally show that few if any cities claim to have been damaged by being connected to the network. In some locations the high speed railway has acted as a catalyst for regeneration or reorientation of a local economy, and there is emerging evidence from the world’s largest high speed experiment, China, that smaller cities are benefitting as pressure mounts on overheating metropolises.

Do we need more rail capacity?

Unequivocally yes. Rail capacity, like air capacity, is defined by the ability of the network to handle more vehicle movements. That capacity no longer exists for rail services to be introduced between London, Blackpool, Shrewsbury and so forth, which is comparable to issues facing London Heathrow airport with its shortage of landing slots. More than £10bn has been spent on refurbishing the West Coast Main Line in the past 15 years, yet much of the capacity gains this programme anticipated have proved illusory. Particularly damaging are the cuts to local trains and station closures which have been made to accommodate more fast trains to London.

The legacy rail network has become more London-centric in the past decade as more high-yield long-distance trains have been introduced, but this has come at the expense of intermediate towns and smaller cities. HS2 is an opportunity to move a sizeable proportion of inter-city traffic to dedicated infrastructure, liberating the conventional network. However, this is not a simple or straightforward process, and reallocating the capacity released by HS2 is one of the biggest tasks facing rail network planners.

What are the viable alternatives, if any?

The main alternative is further incremental upgrading of the three main north-south rail axes. Investment in lines which don't go to London is a tougher proposition -- none of the groups opposed to HS2 have to my knowledge proposed significant spending on links between Birmingham and northern England, which is one of the most underappreciated assets of the HS2 plans. Upgrading of busy conventional railways, as the West Coast Main Line renewal proved beyond doubt, would cost many billions of pounds per corridor, for capacity gains which are at best uncertain.

Reliability of upgraded railways is also in doubt, since the fabric of the infrastructure (bridges, tunnels, embankments) cannot meaningfully be updated. The WCML, despite the near £10bn investment since 1998, is the least reliable route in the UK, as evidenced by industry punctuality figures, with the King's Cross - Edinburgh line not far behind. Both would benefit from HS2 taking some of the strain. This issue is of course highly nuanced – nobody is suggesting that enhancements to the existing railway should not happen, but rather that they are least effective where the capacity shortfall is greatest and the 19th century network is at its most fragile.

What are the economic benefits?

In short railway investment of any kind brings wider economic and social benefits -- if we as a nation did not collectively believe this, we would not provide the level of funding for the whole network that we do. Rail is a vector of economic activity, trade and tertiary industry (the impact of weekend rail disruption on the service economy has not been quantified for example -- perhaps it should be). HS2's main economic benefits are transport related: primarily capacity, but also speed and reliability. Compare the reliability of HS1 in Kent to any other part of the network and the resilience of new infrastructure is immediately apparent.

In certain locations we can expect HS2 to act as a catalyst for development of business and residential zones; more generally, we should expect inward investors to view the country beyond London as a more appealing place in which to develop their activities.

HS2 should also deliver on improving labour market connectivity and productivity. I expect this to be most apparent not on London journeys, but on routes like Birmingham - Newcastle, which would be 55 min quicker by rail under HS2 than at present, with trains potentially running every 30 min. Sir David Higgins’ recent ‘HS2 Plus’ report goes some way to striking the right balance between links to/from the capital and those between regions, within the context that London is the origin or destination of two-thirds of British rail journeys.

Moreover, MPs should ask themselves if they feel 'patch and mend' infrastructure is good enough for our largest regional cities, while London's rail network luxuriates in more than £20bn of capital investment in the 2008-18 period, excluding spending on London Underground.

By that measure, we can certainly afford HS2. There is no option to simply spend £43bn on ‘other stuff’. MPs should back infrastructure investment which is internationally-standard, proven and safe when they vote. HS2 must be built.

This post is based on answers supplied to Sanderson Weatherall for their HS2 blog post, which appears here.

Thursday, 30 January 2014

Northern rail passengers should welcome High Speed 2

|

| Manchester Metrolink's expansion shows that high-quality rail infrastructure in northern England can be funded and delivered successfully. |

The irony of the Green Party traipsing to Oldham’s shiny new light rail alignment was seemingly lost on its pamphlet writers, since the £1.7bn expansion of Greater Manchester’s Metrolink light rail network is a tangible embodiment of the HS2 philosophy – a strong reliance on new-build infrastructure and rolling stock, a mix of new and reopened route alignments, and operating principles borrowed heavily from international best practice. Essentially, the objective is ‘do what works’.

Depressingly, some of the most high-profile calls for HS2 funding to be diverted towards ‘the north’ have come from London. This, of course, has much more to do with ridding affluent quarters of north London and the Home Counties of the spectre of construction work than with an altruistic desire to help passengers in Scarborough or Southport. But, as this blog has noted before, it is local services (those with the lowest yield and greatest reliance on peak-hour patronage, when more passengers are paying full fares) which suffer most when rail capacity becomes scarce.

Hence why – as Shadow Rail Minister Lillian Greenwood pointed out in a House of Commons debate on HS2 earlier this month – the ill-fated £9bn West Coast Route Modernisation programme led to the closure of a score of local stations in rural Staffordshire, and why precious slots on the Stockport – Manchester corridor were taken from Mid-Cheshire Line trains and handed to Virgin expresses.

For those of us who advocate the development of regional railways across northern England and beyond, the notion that axing HS2 would improve the outlook for local rail spending needs to be debunked. Indeed, if northern rail travellers really want better access between a rural and post-industrial hinterland and a clutch of thriving cities, they should be egging on HS2. Why? Because HS2 brings more local rail capacity ‘bundled in’ with it.

Fortunately, policymakers across northern England have worked together over several years to campaign and finally secure a package of investment in rail infrastructure around Manchester (the Northern Hub) and gain a slice of the belated national programme of electrification. This is to be fervently welcomed, and it belies the claim (again, heard most vocally in London and the Chilterns) that HS2 is an ‘all or nothing’ scheme. In any case, a glance at the committed spending for the 2014-19 Control Period immediately confirms what a daft assertion this is.

But equally, Northern Hub is a relatively modest programme involving precious little actual construction of new or expanded railway assets. With a plan to reopen the Standedge tunnel apparently obviated by plans for electrification, the majority of the building work is now concentrated on Salford and Manchester, with the Ordsall Chord and two new platforms on the far western side of Piccadilly station. As Warrington Borough Council made clear in 2012, numerous questions remain about how and where the resulting capacity gains might be used, and just how bountiful they are going to be.

Electrification, meanwhile, is a long overdue intervention that will, over a multi-year timeframe, reduce the cost of operating any half-busy railway. That’s why both the Northwest Triangle and trans-Pennine schemes have been approved, and a taskforce is examining the potential for more routes to follow. But electrification alone has only a very marginal benefit in terms of rail capacity.

In practice, it seems inevitable that most of the benefits of the Northern Hub investment will be felt on the higher-volume Liverpool – Manchester – Leeds corridor, where notable speed and frequency enhancements are already in view. Some intermediate markets stand to benefit too – notably Huddersfield, whose MP, Barry Sheerman, is a noted HS2-sceptic. As an aside, it is strange that Sheerman has not yet voiced his fears over the Northern Hub ‘sucking business activity’ from his constituency to Leeds or Manchester, since its rationale of wider economic benefits is essentially the same as that for HS2.

Less clear are the tangible benefits for local trains on the same routes, already characterised by erratic stopping patters and elderly rolling stock. There is a risk that Flixton and Mossley passengers could face the same scrabble for access rights into Manchester and Leeds as their counterparts in mid-Cheshire already have. Why? Because any serious infrastructure spending dedicated to them has to overcome the hurdle that, typically, regional trains in northern England cover less than 40% of their fixed costs, compared to around 80% for commuter routes in the southeast. This isn’t a surprise: rail does not have as central a role in peak time travel outside London (more than two-thirds of all rail journeys are to or from the capital), and the local economy tends to preclude pricing that would alleviate this investment challenge.

Cancelling HS2 would not alter this paradigm, and it is naïve of the Green Party to suggest that it would. Leaving aside the inevitable reality that the £28bn target cost of HS2 would barely cover further WCRM-style upgrading of the three main lines to/from London, burdening our most cost-sensitive rail services with their own infrastructure overheads would only serve to render their economics more fragile, and risk alienating their ridership as well. Is that what the Green Party and others are really suggesting?

Capacity released by HS2 to enhance as broad a palette of regional services as possible is essential to enhance rail’s share of journeys to and from smaller towns across northern England. A more attractive frequency, timetable and journey time to hubs like Manchester and Leeds, plus interchanges with more reliable HS2-compatible inter-city services at places like York and Crewe, should put local rail on a more cost-effective footing. This hypothesis is not fantasy, either: local authorities in North and West Yorkshire have developed a business case for electrifying the Harrogate Loop line in which connections to HS2 at both Leeds and York feature prominently.

Unlike local rail services, Manchester Metrolink receives no operating subsidy, and as a result it has found it easier to secure funding, from local and national sources, for its capital programme. The Green Party is right to welcome Metrolink to Oldham, yet it appears not to understand how it got there.

Monday, 9 September 2013

HS2: PAC grandstanding obscures welcome scrutiny

|

| The Nürnberg - Ingolstadt high speed line opened in 2006, as part of the phased construction of a high speed corridor between Berlin and Munich. Photo: S Telforth |

But what followed was not entirely a story of fabled Teutonic efficiency. Indeed, local opposition to new railway construction of any sort in Germany is usually vociferous, largely owing to concerns about the noise of freight trains. So it proved with the Berlin – Munich project, which proceeded piecemeal and narrowly survived cancellation on several occasions. Today, around 230 km is still under construction, requiring huge tunnelling efforts through the Thüringer Wald between Halle and Ebensfeld, north of Nürnberg. Completion of the corridor is not expected until the end of 2017 at the earliest, more than 25 years on from the first proposal.

But the continued backing of the federal government for such a locally-controversial programme offers an interesting insight into the ongoing debate over High Speed 2 in the UK. Connecting two of Germany’s most significant cities by international-class transport infrastructure is seen as an economic good in its own right; there was, as far as I can tell, no florid talk of ‘bringing Munich closer to Berlin’, or of ‘rebalancing’, and no pin-head procrastination about how much German business people work on trains.

Which brings us to more sub-tabloid hectoring from Margaret Hodge, the chair of the Public Accounts Committee, whose latest report into the preparations for the HS2 programme has just been issued. To be abundantly clear, this blog is not going to attempt to rebut the measured and valid questions raised by the National Audit Office and the related PAC report, which rightly scrutinises the Department for Transport and HS2 Ltd’s resources and their ability to navigate the project through the tricky Hybrid Bill process.

Especially important is the PAC report’s analysis of the significant contingency applied to HS2 in the current cost estimates, where PAC recommends that DfT ‘should allocate its allowance to specific risks to the programme’. The report also highlights issues of parliamentary timetabling, and DfT’s own resourcing and staffing levels. The latter matters acutely, since DfT and HS2 Ltd are required by the nature of the project to manage a raft of global engineering consultancies which are responsible for the basic design of the railway. If such designs prove to be over-ambitious (as they seemingly were for the first draft rebuild of London Euston), it is HS2 Ltd and DfT, not the consultancy, which gets it in the neck. This interface is worthy of further scrutiny, and PAC/NAO are well placed to do so.

But you wouldn’t know much about any of these details from the grandstanding comments from Ms Hodge issued alongside the report. Instead of sober analysis, we get a thinly-veiled rant which appears to lean rather too much on playing to the gallery. This is important, as it is these comments which have flown immediately into the press and, as a consequence, influenced public perception. Most heinous of these misapprehensions is the suggestion that ‘£50bn would be spent on rail investment in these constrained times’.

This is precisely the opposite of what the government proposes: the whole point of HS2 is to deliver long-term investment over numerous economic cycles, both constrained and otherwise. A funding stream of approximately £1.5bn per annum is already in place from the Crossrail programme; and indeed if Ms Hodge believes spending on transport infrastructure in a downturn is bad thing, where are her headline-grabbing quotes about the £21bn spent on main line rail projects in London in the 2008-18 period?

The government is belatedly adapting its message on HS2 to make more of the rail capacity benefits, which this blog has long viewed as the strongest argument with which to advocate the project. Clearly the government and those it has employed to disseminate this message have struggled to make headway in the wider media, but that shouldn’t excuse a serious failure to listen on the part of Ms Hodge and her colleagues. PAC recommends: ‘The government should publish detailed evidence why it considers High Speed 2 to be the best option for increasing rail capacity into London’ (my italics).

This is a remarkably inaccurate suggestion: HS2 is not purely a ‘London rail capacity project’, since – as I’ve just mentioned – we’ve got quite a few of those taking priority already, although it will benefit commuters using routes from the north into the capital. But equally pressing are capacity constraints elsewhere, notably south of Manchester, in the West Midlands and on key freight axes, all mentioned by this blog passim.

Lastly, we have the sadly predictable monomania about ‘the iPad businessman’. I’m happy to be corrected of course, but as far as I am aware there is no line in the HS2 Economic Appraisal that states ‘the government does not believe that people work on trains’. According to PAC’s report, the benefits of faster journeys to business travellers are based on a series of ‘simplified assumptions’ in line with international practice. PAC dismisses these assumptions as ‘absurd’ given advances in digital technology.

But PAC offers little or no explanation for its own rather extreme view. As transport consultancy SKM Colin Buchanan pointed out recently, it is surely not credible to suggest that working on trains is a particularly new phenomenon. Indeed, it seems a rash assumption indeed that the challenges of connecting to wi-fi, getting a data signal, or charging electronic devices have not some extent suppressed the supposed advantages of working onboard. That’s before we assess external factors such as pricing or overcrowding.

@RichardWellings people worked on trains before invention of wifi, mobiles, laptops and even the biro pen! never understood this argument

— SKM Colin Buchanan (@cbuchanancubed) August 27, 2013

Of course, it is likely that these issues will have been largely resolved by the time HS2 opens in 2032-33, which suggests that updating the survey work now in this area would be of largely academic interest. More worrying on this occasion however is Ms Hodge’s assertion during a PAC hearing that she personally finds the train an ideal place to work. Bully for her, I say, but let us not pretend this is a sound basis for the deliberations of a parliamentary spending committee.

The often-emotive assertions attached to HS2’s status as a ‘high speed’ railway tend rather to overlook the reality that a conventional railway confers almost no benefit, not least because its capacity-enhancing effects would be much reduced, as would its ability to take share from domestic aviation on longer routes (HS2 Ltd estimates that 33% of all Anglo-Scottish journeys on HS2 would transfer from air). Nor is there any evidence to suggest that the long-established correlation between faster journeys and higher revenue is broken.

Both PAC and DfT should reconsider the importance attached to the issue of working on trains, lest we find ourselves endorsing a position where passengers ride trains purely to get some work done. A desire to know how often each passenger toggles between corporate and personal Twitter feeds cannot be allowed to stand in the way of the provision of international-standard transport infrastructure. If it does, PAC, and in particular its chairman, will be required to share some of the responsibility.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. See Railway Gazette International, September 2012, pp54-56.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)